Definitions[]

Spectrum management is

| “ | [p]lanning, coordinating, and managing joint use of the electromagnetic spectrum through operational, engineering, and administrative procedures. The objective of spectrum management is to enable electronic systems to perform their functions in the intended environment without causing or suffering unacceptable interference.[1] | ” |

| “ | the requesting, recording, deconfliction of and issuance of authorization to use frequencies (operate electromagnetic spectrum dependent systems) coupled with monitoring and interference resolution processes.[2] | ” |

| “ | based on three pillars, all equally essential: spectrum allocations, spectrum management and spectrum monitoring. Sound spectrum allocations require extensive international cooperation to ensure that regional, or preferably worldwide spectrum harmonization takes place to deliver the benefits of economies of scale and international roaming] in a way that encourages investment in the development of new technologies without threatening past investments in legacy wireless communications networks.[3] | ” |

Overview[]

Most countries consider radio frequency spectrum as the exclusive property of the state. The radio frequency spectrum is a national resource, much like water, land, gas and minerals. Unlike these, however, radio frequencies are reusable. The purpose of spectrum management is to mitigate radio spectrum pollution and maximize the benefit of usable radio spectrum. Effective spectrum management requires regulation at national, regional and global levels.

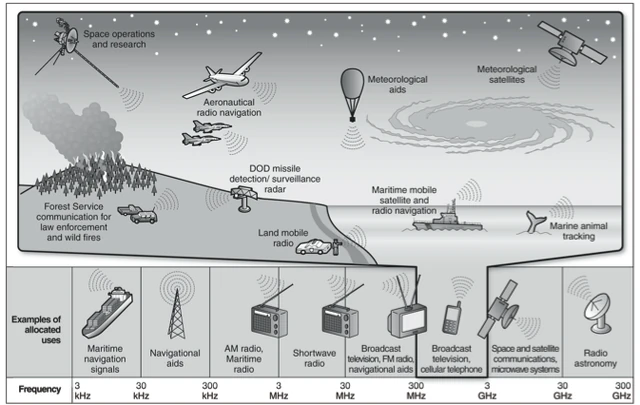

Although radio frequency spectrum is abundant, usable spectrum is currently limited by the constraints of applied technology. Spectrum policy therefore requires making decisions about how radio frequencies will be allocated and who will have access to them.

The goals of spectrum management include: rationalize and optimize the use of the radio frequency spectrum; avoid and solve interference; design short and long range frequency allocations; advance the introduction of new wireless technologies; coordinate wireless communications with neighbors and other administrations. Radio spectrum items that need to be nationally regulated include: frequency allocation for various radio services, assignment of licenses and radio frequencies to transmitting stations, type approval of equipment, fee collection, notifying ITU for the Master International Frequency Register (MIFR), coordination with neighboring countries (as there are no borders to the radio waves, external relations toward regional commissions (such as CEPT in Europe, CITEL in America) and toward ITU.

United States[]

History[]

The U.S. history of spectrum management is as old as the advent of radio communications. In 1906, the year when speech and music were first broadcast using radio, the first international radio conference was held. In the United States, widespread interference caused by unchecked transmission resulted in the Radio Act of 1912. The 1912 Act required the registration of transmitters with the Department of Commerce, but did not provide for the control of their frequencies, operating times, or station output powers. Thus, the 1912 Act was largely unsuccessful.

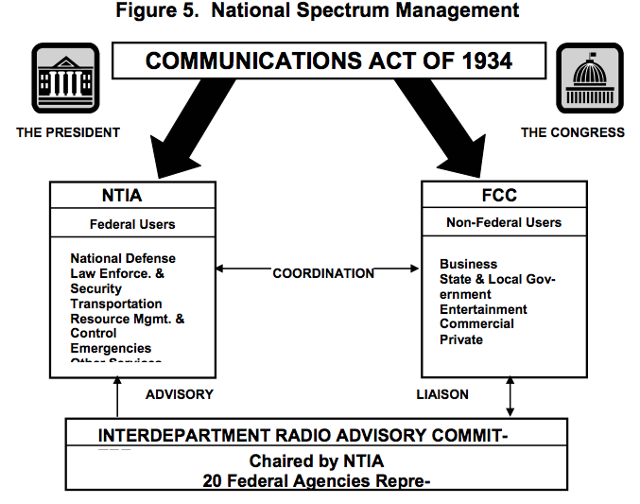

In 1922, U.S. government users of the spectrum gathered under the Secretary of Commerce to form the Interdepartment Radio Advisory Committee (IRAC) to coordinate U.S. Government use of the spectrum. The Government's use of the spectrum was more easily coordinated than the public's because the IRAC represented all federal users and such cooperation was mutually beneficial.

The Radio Act of 1927 established the Federal Radio Commission, which was shortly replaced by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) under the Communications Act of 1934 (the "Act").[4] The FCC is authorized to develop classes of radio service, allocate frequency bands to the various services, and authorize frequency use to non-federal users.

In addition, Section 305 of the Act preserves for the President the authority to assign frequencies to all federal government-owned and operated radio stations,[5] as well as the authority to assign frequencies to foreign embassies in Washington, D.C., and to regulate the characteristics and permissible uses of the government's radio equipment.[6] The President has delegated these powers to the Assistant Secretary for Communications and Information who is also the Administrator of NTIA.[7]

Today[]

As shown in Figure 5, the result of the Act is that spectrum management, in the United States is split between NTIA and the FCC, with inputs from other agencies in certain circumstances. NTIA manages the federal government's use of the spectrum while the FCC manages all other uses. However, the Act does not mandate specific allocations of bands for exclusive federal, non-federal, or shared use; all such allocations stem from agreements between NTIA and the FCC.

Radio frequency spectrum is managed by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) for commercial and other non-federal uses and by the National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA) for federal government use.

The demand for spectrum is intense and the FCC has responsibility for allocating spectrum among the various users. As wireless broadband networks continue to shift from traditional voice networks to those that incorporate a wide range of advanced broadband services, they will need more spectrum in wider contiguous bandwidths.

The FCC, over many years, has developed and refined a system of exclusive licenses for users of specific frequencies. Auctions are a market-driven solution to assigning licenses to use specific frequencies and are a recent innovation in spectrum management and policy. Previously, the FCC granted licenses using a process known as "comparative hearings" (also known as "beauty contests"), and has used lotteries to distribute spectrum licenses.

As wireless technology moves from channel management to network management, spectrum policy going forward may entail encouraging innovation in network-centric technologies and their applications.

How this spectrum should be allocated among the myriad users, the size of the blocks allocated, and whether any special considerations should be given to specific entities (e.g., rural or small providers) that bid in spectrum auctions are among the issues confronting policymakers.

The need to harmonize spectrum allocations worldwide is also a key policy issue. Harmonization enables network operators and equipment manufacturers to realize significant economies of scope and scale and facilitates global interoperability for consumers.[8]

References[]

- ↑ Electronic Warfare, at GL-13.

- ↑ Joint Publication 6-0, at III-16.

- ↑ Tactile Internet, at 17.

- ↑ 47 U.S.C. §151 et seq.

- ↑ See id. §305(a).

- ↑ See id. §305(c).

- ↑ See Section 103(b)(2) of the NTIA Organization Act (codified at 47 U.S.C. §902(b)(2)); see also Executive Order 12046.

- ↑ For a discussion of spectrum policy and other issues relating to wireless broadband policies see Wireless Communications Association, "A National Wireless Broadband Strategy" (full-text).

Source[]

- "United States" section: Spectrum Policy for the 21st Century – The President's Spectrum Policy Initiative: Report 1, Recommendations of the Federal Government Spectrum Task Force, at 8.

See also[]

- Battlespace spectrum management

- Commerce Spectrum Management Advisory Committee

- Electromagnetic spectrum management

- Office of Spectrum Management

- Radio Spectrum Management

- Radiofrequency Spectrum Management

- Spectrum Management: NTIA Planning and Processes Need Strengthening to Promote the Efficient Use of Spectrum by Federal Agencies

| This page uses Creative Commons Licensed content from Wikipedia (view authors). |

|